The UK corporation and withholding tax treatment of guarantee arrangements and related payments is complex. Once the legal nature of the various guarantee relationships is understood, the UK tax analysis can be applied. However, even then difficulties can emerge in determining the UK tax corporation and withholding effect of guarantee arrangements given the lack of case law, guidance and legislative provisions specific to guarantees.

When entering into finance arrangements it is common for creditors to require someone, generally another group company, to guarantee a borrower’s obligations. The requirement to enter such guarantee arrangements will be commercially driven as part of the broader security package requested by the creditor. Whilst guarantees may be commonplace, the UK tax position, especially when guarantees are called, can be complex.

This article provides an overview of the key UK corporation and withholding tax considerations to bear in mind on guarantees. For these purposes, we have assumed that the borrower, guarantor and creditors are UK tax resident. This article does not address any other issues arising from guarantee arrangements, including non-UK issues (for example, where a non-UK company is guaranteeing obligations of a UK borrower) which should always be checked and are not always intuitive.

Entry into guarantees

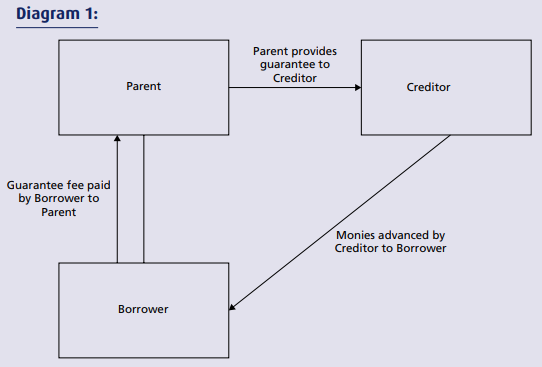

Before considering the UK tax aspects of guarantees, it is important to understand the nature of the arrangements. Put simply, in a financing context, under a guarantee the guarantor promises the creditor that the borrower will perform its obligations under the financing arrangements. In addition, the guarantee will typically include indemnification obligations requiring the guarantor to pay amounts owed to, and make good any loss suffered by, the creditor following borrower default. A guarantor is not under any obligation to pay under a guarantee until a call has been made (see Diagram 1 below).

From an accounting perspective, given the contingent nature of any guarantee arrangements it is unlikely they would be recognised as liabilities on a balance sheet upon entry.

As the starting point from a UK corporation tax perspective in relation to financial obligations is generally to follow the accounts, simply entering into a guarantee in and of itself would not be expected to give rise to adverse UK tax consequences. However, a few points to note:

- Borrowers should consider whether a guarantee affects interest deductibility when calculating a company’s profits under the UK transfer pricing rules (broadly, the existence of a guarantee from a connected party is effectively ignored when evaluating what could and would be lent to a borrower at arm’s length).

- Where a guarantee fee is paid, such fee would be generally deductible for a borrower, and generally taxable for a guarantor, for UK corporation tax purposes (albeit within a UK group the deduction and the income may offset to produce a neutral outcome).

- UK transfer pricing rules will also look at the guarantee arrangements to determine the appropriate amount of fee (if any) payable by the borrower to the guarantor for the provision of the guarantee. Where a fee is payable it may be adjusted for tax purposes to reflect arm’s length arrangements; where no fee is payable an arm’s length fee may be imputed. The application of transfer pricing to guarantee fees depends on the precise circumstances of the arrangement in question, including what benefits (other than the fees) a guarantor obtains from providing the guarantee. Where the guarantor and borrower are both UK tax resident, the impact of transfer pricing will likely be limited because of the symmetry resulting from any corresponding adjustments.

- There should be no UK stamp duty or VAT concerns upon entry into a guarantee.

Given the above, it is perhaps unsurprising that, from a UK tax perspective, there is limited focus on guarantees when negotiating finance arrangements (although to note that in a number of other jurisdictions the rulescan vary and there can be VAT, stamp tax or withholding consequences from simply entering into a guarantee).

As a starting position, creditors will often assert they will not take any withholding risk in respect of future guarantee payments (which can be compared to the position with respect to withholding tax on interest payments from a borrower which, rarely, provide an unqualified “gross-up” (under the LMA documents the creditor is only grossed up if it is a Qualifying Lender)). Of course, whether that is acceptable will depend on a host of factors (and the jurisdictions involved); whether it matters will also generally only become relevant if the borrower defaults and the guarantee is called.

Default

Classification of guarantee for UK corporation tax purposes following call

The UK tax classification of a loan advanced by the creditor to the borrower is clear: it is a loan relationship for UK corporation tax purposes (on the basis that it is a “money debt” arising “from a transaction for the lending of money”) subject to the specific corporation tax rules applicable to loan relationships.

Conversely, from a UK corporation tax perspective, upon entry into a guarantee there is no debt or liability; no amount is owed by the guarantor to the creditor under the guarantee simply a contingent contractual promise. Essentially, the guarantee is a “nothing” for UK corporation tax purposes at that point.

However, where the guarantee is called following borrower default, although there may well be a “money debt” for UK corporation tax purposes, the UK tax authority (HMRC) considers that such “money debt” does not arise “from a transaction for the lending of money” and so not a loan relationship for UK corporation tax purposes. This is not, however, a universally accepted view. An alternative view is that the guarantor becomes a party to the original loan relationship with the original creditor when the guarantee is called.

Notwithstanding, the distinction may be theoretical in many cases as HMRC consider that, once called, even if not an actual loan relationship, the guarantee would “likely” be a relevant non-lending loan relationship (and so be treated as a loan relationship for UK corporation tax purposes in the same way as an actual loan relationship). Whether this is the case would turn on satisfaction of prescribed legislative conditions.

Impact of calling a guarantee on the borrower/guarantor relationship

Other than the potential for a fee to be payable or, under transfer pricing rules, to be deemed to be payable by the borrower to the guarantor, entry into a guarantee should not create a relationship as between the borrower and guarantor. However, this changes when the guarantee is called and the guarantor makes a payment.

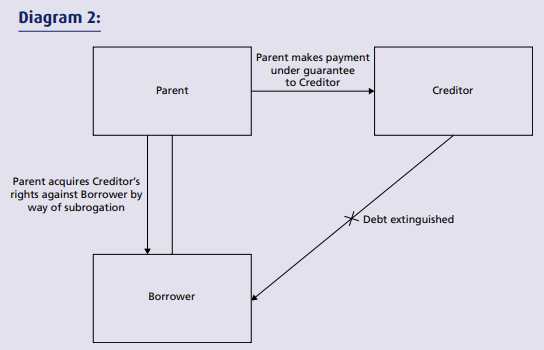

In those circumstances, following satisfaction of the guarantee, generally as a matter of English law the guarantor acquires the creditor’s rights against the borrower by way of subrogation. That is, the guarantor effectively replaces the original creditor as the creditor on the original lending. Subrogation may occur by operation of law or under a subrogation clause in the guarantee (see Diagram 2).

From a UK corporation tax perspective, HMRC’s view is that, following subrogation, the borrower owes a “money debt” to the guarantor, such “money debt” being either a loan relationship or a relevant non-lending relationship for UK corporation tax purposes.

UK corporation tax consequences of guarantee payments

Guarantor

For the guarantor the UK corporation tax treatment of a guarantee payment is complex. As noted, HMRC’s view is that there is no loan relationship and, even though the guarantee is a relevant non-lending relationship after being called, HMRC’s position (following IRC v Holder & Holder (1930) 16 TC 540) is that any payment (including payments in respect of interest) made by a guarantor to creditors under a guarantee “has lost the character of interest in the guarantor’s hands” with the result that amounts payable are not interest payments. On that view, no UK corporation tax deduction is available to the guarantor against its profits on payments made under the guarantee under the loan relationship regime.

Outside the loan relationship regime, applying general principles and looking at whether payments under a guarantee are of a revenue or capital nature, in most cases, a guarantor would not usually have provided the guarantee in the course of its trade with the result that guarantees are generally regarded as capital liabilities. Accordingly, a payment under a guarantee will likely be treated as a capital payment for which the guarantor will be unable to claim a deduction (and, in any event, it is unlikely that it could be said that the guarantor is making the payment wholly and exclusively for the purposes of its trade).

Even under the alternative view mentioned above where the guarantor becomes party to the loan relationship following call, subject to very limited exceptions, generally the guarantor may not obtain any effective relief for the guarantee payment where the accounting treatment does not reflect any debits.

The position is not improved by subrogation. Following subrogation, HMRC’s view is that the amount owed by the borrower to the guarantor is a loan relationship (with resultant UK tax consequences), although again this is not a straightforward analysis.

However, as most guarantees will be provided by group companies were the guarantor to impair or release the debt owed by the borrower, in most cases the guarantor would not be able to claim a debit for UK corporation tax purposes in respect of any such impairment or release. Accordingly, where there is the risk of borrower default and the guarantee being called, it may be preferable for the guarantor to pre-fund the borrower so that it can avoid default.

Borrower

From the borrower’s perspective, where the guarantee is not fully satisfied but the creditor agrees that the debt will be discharged in full (eg on a debt with a face value of £100 the guarantor pays an agreed amount of £80 to the creditor, but is owed the full £100 rights as against the borrower as a result of subrogation), one initial question is whether the so-called “deemed release” rules are implicated which would trigger taxable income for the borrower.

Where those rules are engaged consideration should be given to whether any exemptions are available to mitigate the taxable income that would otherwise arise to the borrower.

Any subsequent impairment or release of the amount owed by the borrower to a group guarantor following subrogation would not be expected to result in any UK corporation tax cost for the borrower.

Creditor

From the creditor’s perspective, receipt of the guarantee payment should be treated in the same way as receipt of the equivalent payment from the borrower:

- if the guarantor makes a payment in respect of interest that should be treated as interest on a loan relationship for the lender;

- if the guarantor repays the principal outstanding, repayment of principal would not normally result in a UK tax cost for the lender, but will depend on the circumstances (for instance, if the creditor impaired the debt) and accounting treatment.

Finally, where satisfaction in cash is not possible, a creditor may accept satisfaction (or part satisfaction) of the guarantee call through an issuance of securities. This presents additional complications, including whether this leads to a connection between the guarantor group and the creditor and whether any tax grouping is broken.

UK withholding tax consequences of guarantee payments

Under UK domestic law, payments of annual interest (broadly, outstanding for a year or more) with a UK source (paid by a UK person or otherwise where the source of the funds are UK based) are subject to withholding tax at 20% unless a domestic exemption is available (such as the UK-UK corporate exemption, quoted Eurobond or Qualifying Private Placement (QPP) exemptions) or relief is available under a double tax treaty. This is usually played out in finance documentation in the “Qualifying Lender” definition and associated clauses (and generally a Qualifying Lender is one to which a UK borrower may make gross payments of interest).

From a UK withholding tax perspective, there is no settled view on whether guarantee payments take the same nature and source as the obligation being discharged; there are two schools of thought:

- the first is that the guarantee payment retains the characteristic of the underlying obligation so that, if the payment is in respect of UK source interest, the guarantee payment should be treated in the same way;

- the second is that the guarantee is a separate money debt from the underlying obligation so the withholding analysis is separate from the analysis in respect of the underlying obligation.

Under the first approach where the guarantee payment assumes the nature of the debt obligation, withholding tax would be due if the guaranteed payment is in respect of annual interest and paid from a UK source. This may also allow the guarantor to benefit from any exemption applicable to the underlying obligation – for instance, the quoted Eurobond or QPP exemptions. However, the difficulty with this approach is that it is not the analysis that HMRC applies to guarantee arrangements generally (HMRC regard the guarantee as being a separate money debt to the underlying obligation).

Under the second approach where the guarantee is regarded as a separate obligation, the guarantor should only be required to withhold UK tax to the extent that the payment is treated as an “annual payment” for UK tax purposes (on this view the payment should not be “interest” because it is not a payment for use of money over time).

As with the UK corporation tax position, it may be possible to avoid this uncertain withholding tax analysis through the guarantor putting the borrower in funds, rather than make guarantee payments itself.

If a UK guarantor does make payments and a UK withholding tax obligation arises in relation to which no domestic exemption applies, it may be possible for the parties to mitigate withholding tax leakage through a claim under a double tax treaty. This may be through the “Interest” article (noting here that “interest” in a treaty may have a wider meaning than under UK domestic law) or under the “Other Income” article. The procedures to enable a payer company to pay without deduction may be different depending on the characterisation of the payment.

In its Double Taxation Treaty Passport (DTTP) Scheme guidance, HMRC confirms that it regards the date from which the guarantee is called upon (and the guarantor assumes liability for payments) as the beginning of a new loan relationship amenable to the use of a passport. HMRC may also grant “one-off” treaty clearance applications, as well as DTTP applications, in respect of guarantee payments where ther is a concern that a UK withholding obligation would arise in respect of that payment. It thus seems that HMRC adopt a pragmatic approach regardless of whether the withholding arises through the payment being “interest” or an “annual payment”.

Release

Sometimes guarantors may make payments to creditors to secure the release of their obligations under the guarantee. Guarantors may make such payments either before borrower default (eg if the guarantor is being wound down or sold), or after borrower default (eg as part of a compromise arrangement between the guarantor and the lender). UK tax points to consider include:

- Where the borrower has not defaulted, in most cases the guarantor will not be able to claim a deduction for UK corporation tax purposes in respect of the payment. Further, because no money debt has crystallised, there should be no adverse UK corporation tax consequences for the guarantor on the release of the guarantee (which remains a contingent liability).

- Where the borrower has defaulted and the guarantee called, theposition is more complex. In this scenario, the obligation to make the payment under the guarantee would have crystallised (a current liability) and so, on HMRC’s analysis, a “money debt” is owed. Subject to the accounting treatment, although the guarantor may not be able to claim a deduction in respect of the amount paid, in some cases, the guarantor may be required to recognise any shortfall between the amount it pays and the amount released as taxable income (although where the borrower and guarantor are UK resident, symmetrical (neutral) tax treatment should be possible).

Concluding remarks

Walking through the lifecycle of a guarantee reveals that the UK corporation and withholding tax position is complex and not free from doubt exacerbated by the lack of case law, guidance and legislative provisions specific to guarantees. Tax issues may not be front of mind when guarantees are entered into, and defaults are not contemplated. It should not be assumed that guarantee arrangements (whether with a UK or overseas nexus) are tax neutral.